Perfectly timed for the cold season, students in Dr. Milne’s Chemistry class learn about a phenomenon that is called “freezing point depression.”

Chemically speaking, freezing point depression involves the intentional decrease of the freezing point of a solvent following the addition of a non-volatile solute. Common examples include salt in water and alcohol in water.

When road crews spread a salt (calcium chloride) on icy roads to melt ice, they help transform water from its frozen, solid state into a more liquid state, rendering roads safer for driving.

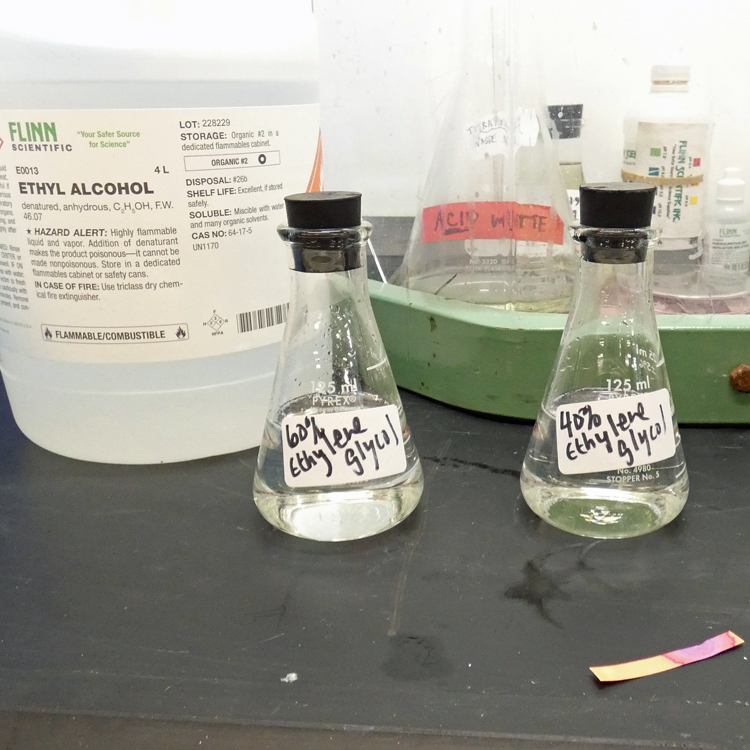

Another practical application is windshield washer fluid which benefits from the addition of ethylene glycol to help prevent the dangerous re-freeze of the sprayed fluid on the cold surface of a car’s windshield.

Perhaps the most widespread, daily application of the chemistry in freezing point depression is radiator fluid, where antifreeze is added to the cooling system. A solution of 60% antifreeze and 40% water will produce a freeze protection of up to -55˚ C. For best overall performance, a 50% solution is commonly used for engine protection in temperatures between -35˚C and 108˚C.

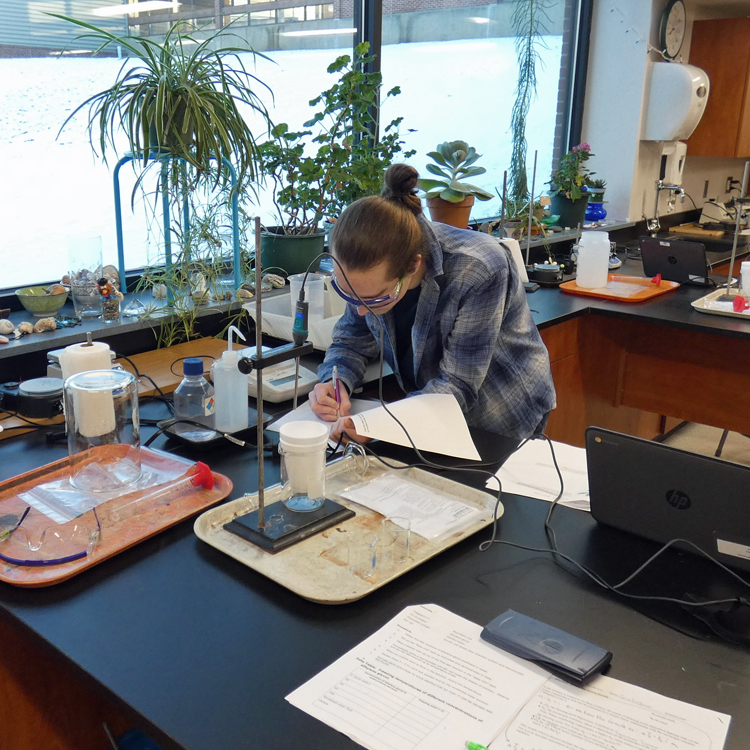

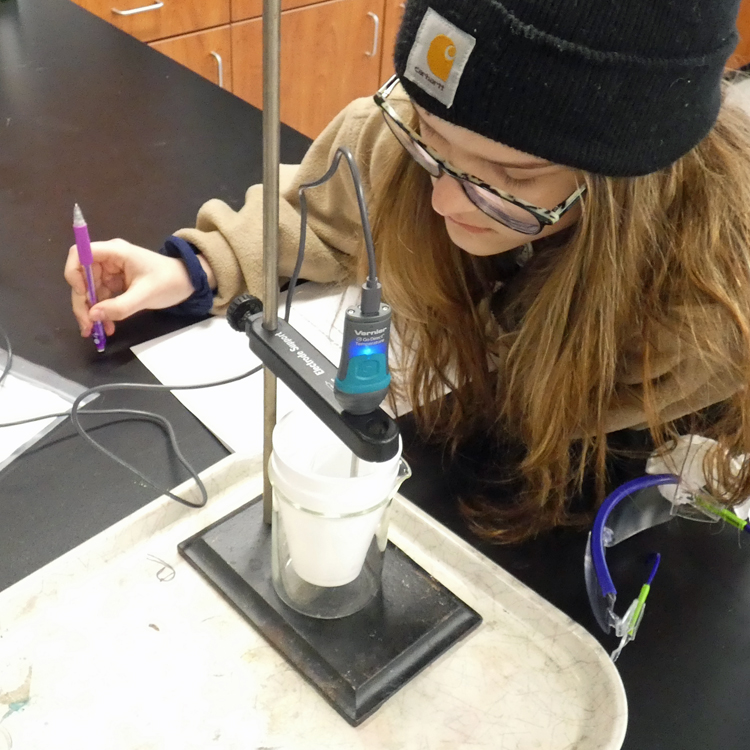

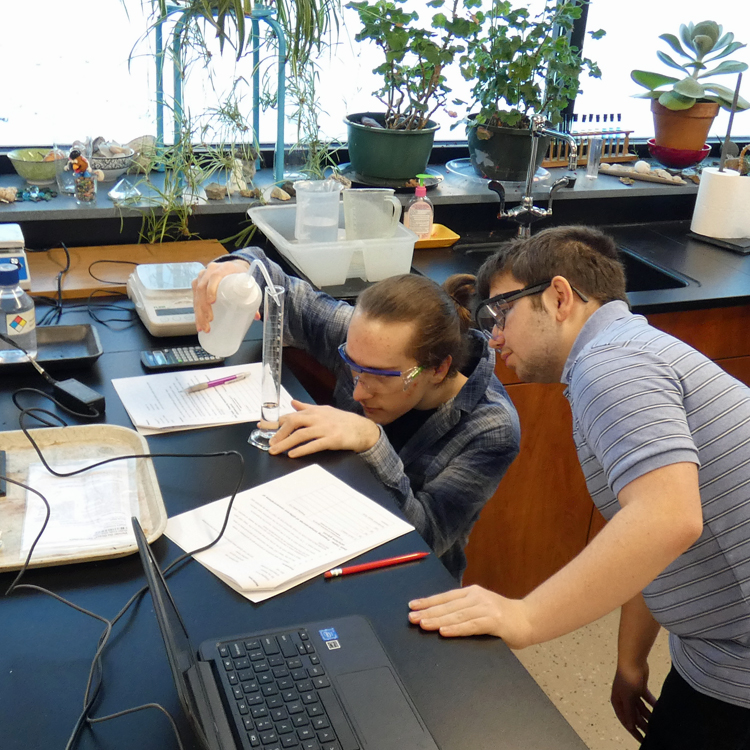

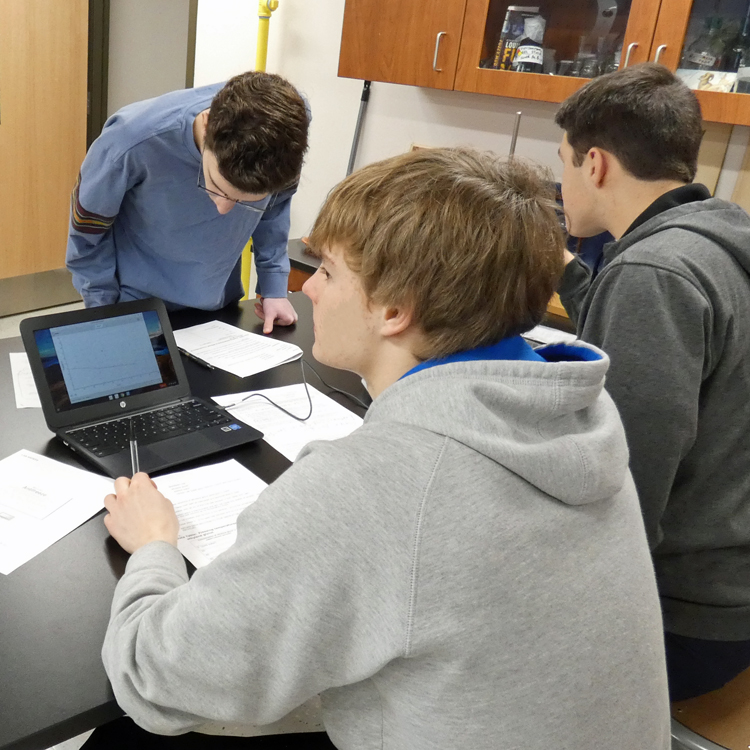

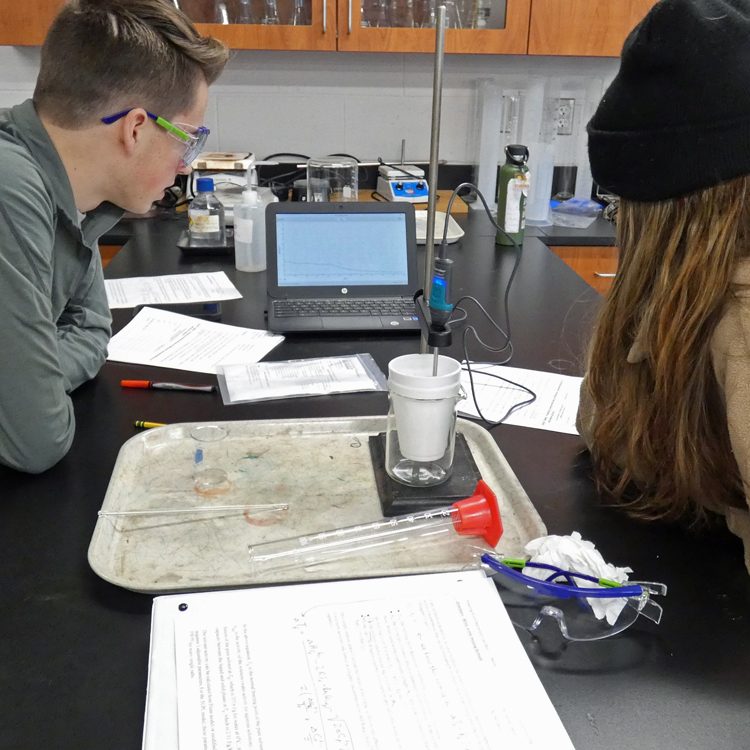

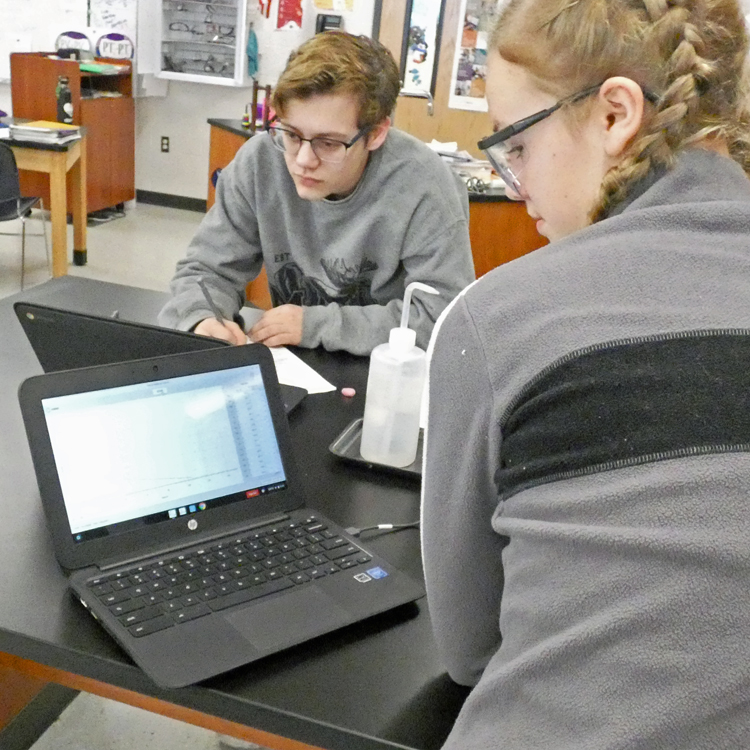

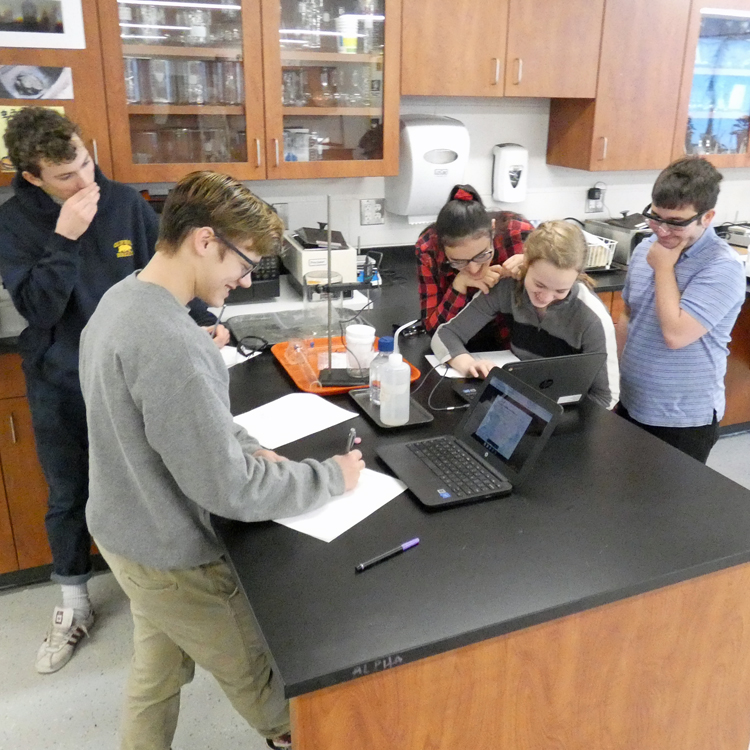

In a number of lab activities, students added different solutes to pure liquids to ascertain how these solutes would lower the freezing point. They created five test solutions in beakers and set up a “deep chill” bath using dry ice. Using USB-connected Vernier temperature sensors and the Lab Quest data collection system of their Chromebooks, students then recorded data as temperatures dropped and crystallization of the solution could be observed.

The photos below show students during different stages of the experiments.